The following article was written by Giles Coghlan, Chief Currency Analyst at HYCM.

A Brief History

Giles Coghlan, Chief Currency Analyst at HYCM

In some ways, gold is like the ugly duckling of asset classes. Long before economist John Maynard Keynes famously called it the “barbarous relic” there was a history of various commentators referring to the yellow metal as “a relic of barbarism.” Incidentally, the Keynes quote is often taken out of context. It was the gold standard, not gold itself that he referred to as a barbarous relic.

Keynes was against the UK returning to the gold standard after WWI and was a vocal critic of the chancellor of the exchequer, Winston Churchill, when he reintroduced it in 1925. He would oppose it until Britain finally went off the gold standard in 1931. Keynes was against the gold standard because having its currency pegged to gold wouldn’t permit the UK to implement the type of expansionary policies (currency creation) that would allow it to recover from the costs of WWI.

The second time in recent history that gold would undergo a big change in narrative was during the Bretton Woods system that lasted from 1944-1971. With the US dollar newly introduced as the world’s reserve currency (albeit backed by gold), the narrative gradually started to shift away from the gold standard itself, to a global financial system in which the strength of the US dollar made it as good as, if not better than gold itself. After all, US dollars earned interest and were much easier to move around and conduct global trade with.

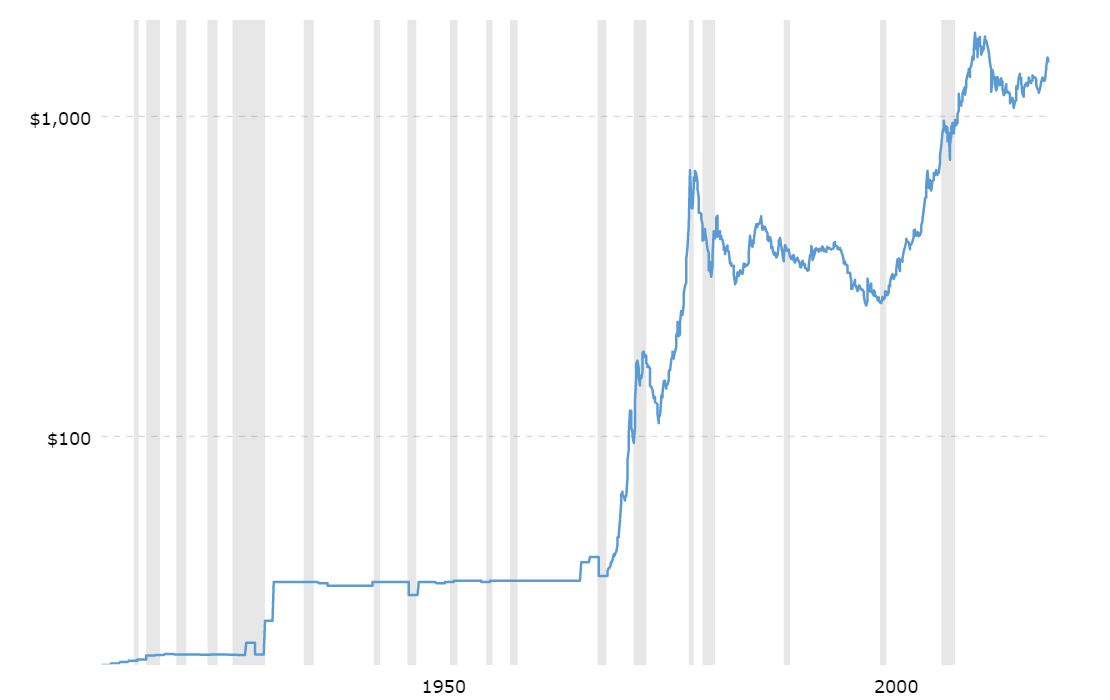

Gold’s narrative would once again change in the late 1970s. After having been relegated to a sort of backstop for the US dollar in the Bretton Woods agreement, it was removed entirely from the picture in 1971 when president Nixon closed the “gold window.” This revoked US dollar convertibility with gold at the fixed rate of $35 per troy ounce. The closing of the gold window effectively ushered in the “fiat” era that we live in today, where currencies are not backed by anything other than trust in their respective governments.

Image Source: https://www.macrotrends.net

Gold Set Free?

An interesting consequence of Nixon closing the gold window is that it effectively allowed gold to be something other than the perceived barbarous relic used by governments to manage their trade deficits and to fix the value of their currencies. Indeed, many have forgotten that the 1970s were the best decade that gold ever had. It went from a low of $34 per ounce in 1970 to a high of $693 in 1980; that’s a staggering 1938% increase in ten years.

When US dollars ceased being backed by gold, gold went back to being what it always has been; a safe haven asset, a store of value, a hedge against inflation and a bet against the existing financial system of the time and business as usual. In other words, by being removed from the realms of monetary policy, it too could float freely and be valued by the market instead of being artificially pegged. It pays to remember that after the gold window was effectively shut, there was quite some uncertainty as to what role gold would play in a modern economy. You can see that uncertainty reflected in the fantastic run that the metal made between 1970 and 1980.

What’s so Good About Gold Anyway?

Gold exhibits certain properties that are quite hard to overlook or mimic. It’s a rare element that can’t be broken down further into any other substance. There’s a fixed supply of it on the planet that has remained the same in the 4.5 billion years that the earth has existed. Unlike other elements, it doesn’t tarnish or degrade in any way, meaning that not only can its value be passed down to your ancestors, but that it will remain long after your ancestors and everyone else are gone.

All this is just another way of saying that gold is permanent, quite a compelling idea when it comes to preserving value, something which is constantly shifting and changing. You can understand why we’ve been obsessed with it for many thousands of years. In a world where everything constantly changes, gold seems to offer a much-needed sense of stability.

The Great Recession

The second major bull market run that gold underwent in recent memory took place during the Great Recession of 2008. Gold went from a low of around $700 in 2008 to a high of around $1900 in 2011. It’s no coincidence that this spike took place while governments frantically printed money in order to keep their banking systems afloat. In this period global debt rose to new highs while interest rates dropped to the lowest in around 5000 years.

One of the simplest and most cogent bull cases you can make for gold is that unlike cash, stocks, and bonds, gold is no one else’s liability. In a debt-based economic system, one where crises like 2008 occur when hidden risks lurk everywhere, an indisputable asset like gold not only has a place but also performs a vital function.

Gold Keeps Us Honest

For the same reasons that Keynes took issue with it, gold’s qualities make it unsuitable as a basis for a modern monetary system. It doesn’t allow central banks to completely control the currencies they manage. This is because under a gold system there are certain limitations imposed on supply by the very laws of physics, which is also why it’s considered by many to be so barbarous a relic. It doesn’t allow for the types of financial innovations that have grown side by side with our modern age. In short, the iPhone probably wouldn’t have been invented under a gold standard. Keynes knew this.

It’s a fascinating aspect of gold’s evolving story. We can leave the debate about whether it’s suitable as the basis of a modern economy to the economists. What’s difficult to debate is that the features that make it troublesome for economists and policymakers, also make it a valuable place to park capital when the future becomes uncertain. This is the role it has started to play again in 2019.

The Next Bull Market?

After three rounds of quantitative easing and similar policies across Europe, the UK, and Japan, immediate fears of global collapse receded. The architects of a new era of unconventional monetary policy congratulated themselves for having averted the collapse of the global financial system. Gold plummeted from its highs, losing almost half of its value by the end of 2015. It would remain range-bound between the high 1300s and low 1100s until June of this year when it finally broke resistance, surging by around 15% at its recent peak at the beginning of September.

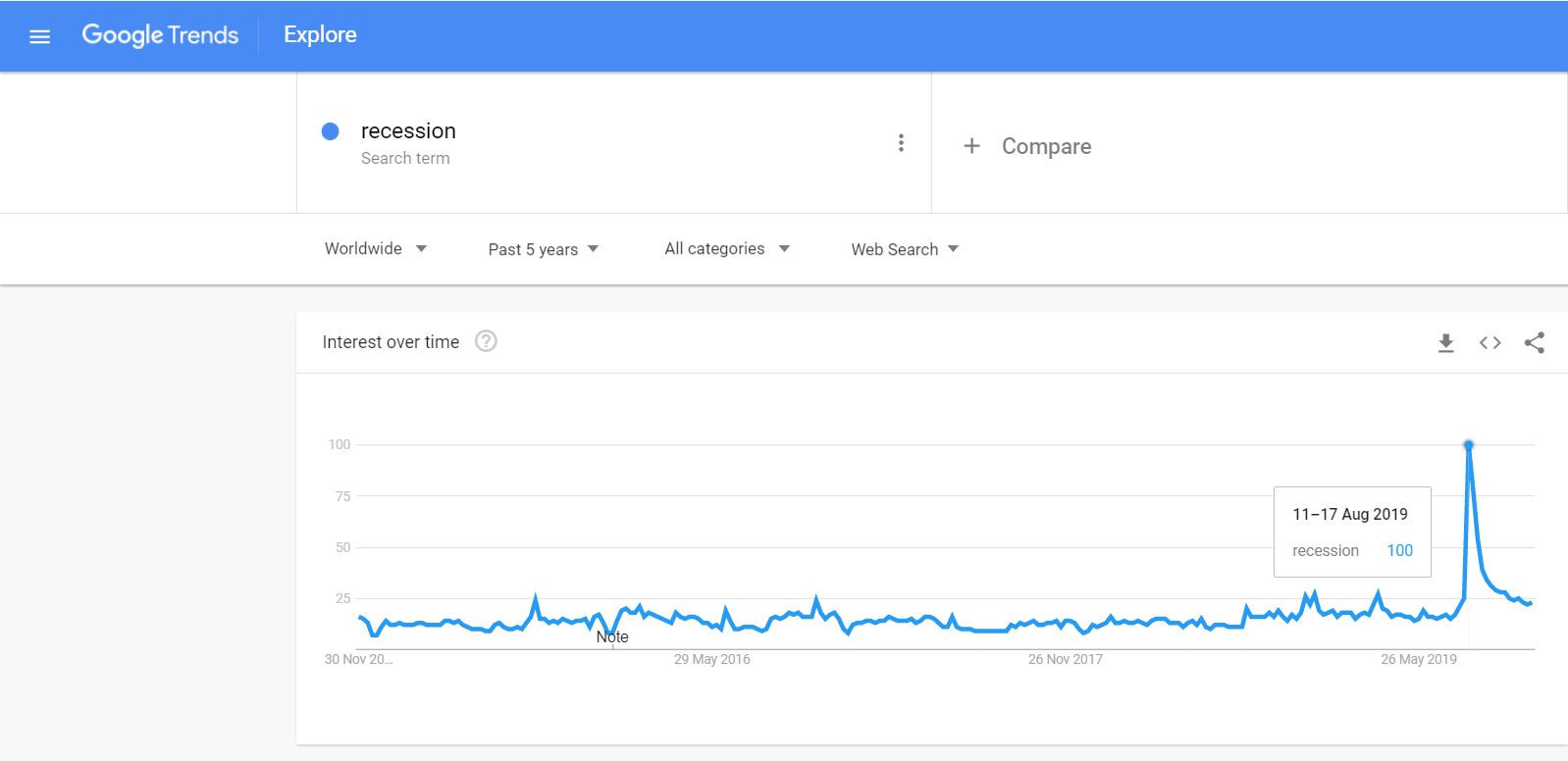

It’s no coincidence that August was also the month that the US yield curve inverted. Yield curve inversion is when short-term US treasuries pay more interest than their long-term counterparts. It’s a popular and highly reliable recession indicator, which explains why Google searches for the term “recession” peaked in August.

Image Source: https://trends.google.com

Factor in the global uncertainty over Brexit and the US-China trade war, both of which are unfolding against a backdrop of a slowdown in global growth, and you start to develop an argument for why gold may be in the early stages of another secular bull market.

Recent manufacturing data show that the US is officially in a manufacturing recession, as defined by three consecutive months of negative growth. German PMI data reveal the same thing about Europe’s manufacturing powerhouse. We also have the thorny topic of low or negative rates, a legacy of the financial engineering we conducted in the wake of 2008, one that we have been unable to undo. The US Federal Reserve’s efforts to reduce their balance sheet and raise interest rates caused the US economy to sputter, which was followed by a quick U-turn in policy by the Fed from tightening to easing again. It also resulted in the liquidity shortages we’ve been seeing in the recent repo market spikes.

Finally, let’s not forget that further quantitative easing is firmly back on the agenda now, both in Europe and the US. Former ECB president Mario Draghi resumed Europe’s QE program before handing over the reins to Christine Lagarde. Over in the US, Fed chairman Jerome Powell has initiated repo market interventions many view as QE by another name. These are all the traditional alert signals that cause investors to start looking at gold again.

Finally, perhaps the most compelling piece of evidence: gold has broken all-time highs already. It has done so when priced in currencies other than the US dollar. Gold peaked against the euro at just under €1400 in 2012, at the height of the EU debt crisis. In September of this year, it broke €1400, trading as high as €1415 before retracing. The same is evident when you pair gold with any of a number of currencies that are not the US dollar. With GBP, gold recently broke its former highs by around 7%, against the Aussie dollar it’s still up almost 17% above its previous all-time highs, even after this recent pullback.

Of course, just as gold loves uncertainty, anything that reduces uncertainty tends to see capital fleeing gold and re-entering riskier assets. If the US-China trade deal is signed, the US economy and the Eurozone both recover making the bull picture for gold no longer so clear. This is something to keep in mind when investing in the precious yellow metal. One thing is clear if you were ever contemplating gold now is a highly interesting time to look into it.

High Risk Investment Warning: Contracts for Difference (‘CFDs’) are complex financial products that are traded on margin. Trading CFDs carries a high degree of risk. It is possible to lose all your capital. These products may not be suitable for everyone and you should ensure that you understand the risks involved. Seek independent expert advice if necessary and speculate only with funds that you can afford to lose. Please think carefully whether such trading suits you, taking into consideration all the relevant circumstances as well as your personal resources. We do not recommend clients posting their entire account balance to meet margin requirements. Clients can minimise their level of exposure by requesting a change in leverage limit. For more information please refer to HYCM’s Risk Disclosure.