The following article is courtesy of Retail FX broker Aetos Capital Group.

Part II (for Part I click here)

Queen’s rulings in finance weakened

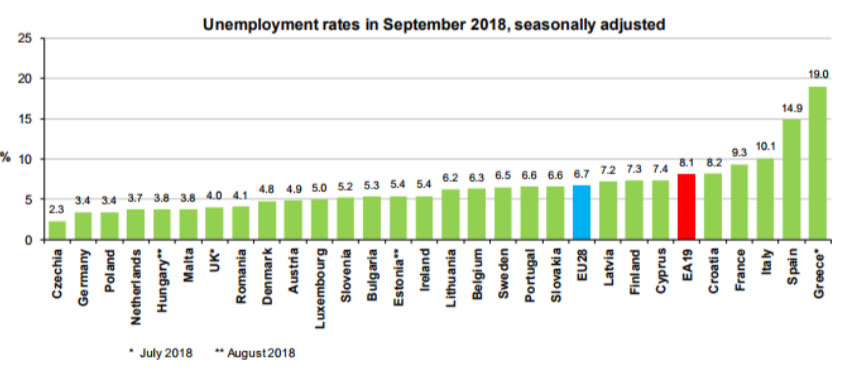

Data released by Eurostat shows that, in September 2018, unemployment rates in France, Italy and Spain were 9.3%, 10.1% and 14.9%, respectively, with the 3.4% unemployment in Germany, who highlights it as the lowest among the 19 countries in the Eurozone. The landscape is a miniature of the Eurozone’s economic situation since the last decade.

In the wake of the 2008 financial crisis, Germany has emerged as Europe’s bellwether for the economy with the “draconian” reforms on its redundant welfare programs, labor market and pensions under Merkel and her predecessors. From 2007 to 2013, the share of government debt in GDP of 19 countries in the Eurozone soared by 26.6%. Treasury yields of the debt-laden “PIIGS,” namely Portugal, Ireland, Italy, Greece and Spain, continued to soar with their sovereign ratings at risk. At that time, Germany, which had recovered its position as Europe’s economic engine by means of strict fiscal discipline, was unquestionably the biggest contributor to the Eurozone.

Many countries expected Germany to lend a helping hand. During a long-term political seesaw struggle, Ms. Merkel imposed harsh reform requirements on her aid plans, including deep cuts in government spending and budget deficits, and sweeping changes to the social welfare system, which made most of the European countries awake with a start out of the hotbed of high debt and high welfare. Mired in sovereign debt crises, they eventually agreed to Germany’s demands, and Ms. Merkel was dubbed the “queen of cuts”.

In fact, during the years when Germany implemented the strict European fiscal plans, there were always voices within the EU that the requirements of fiscal balance should be relaxed and vigorous stimulating policies adopted. Merkel’s control over German politics, however, remained unchallenged, as was Germany’s leadership over the EU. Guided by “Merkelism,” the government debts as a share of GDP among the 19 Eurozone countries have been declining since 2014, a seemingly sign that Merkel almost single-handedly resolved the European debt crisis. However, one man’s meat may be another man’s poison. Those European countries that made reforms in pursuit of financial balance, in response to the call of Germany, only found themselves confronted with more serious economic problems in the years that followed.

Ms. Merkel, a firm believer in the principle of fiscal balance, having chosen not to seek political office upon the end of her term as chancellor in 2021, would likely see the abolition of her long-advocated fiscal policies. On the day she announced she would not run the re-election, the German stock index DAX 30 closed up 1.20%, France’s CAC 40 0.44%, and the FTSE Euronext 300 index 0.88%. As the German right-wing party celebrated their victory, capital also seemed to be giving vent with soaring stock index to its pent-up emotions, which had for several years been suppressed by Merkel’s austerity policy. More symbolically, on the very same day, Philip Hammond, Chancellor of the Exchequer, rolled out his budget for the autumn of 2018, with a focus on spending increases and tax cuts. In the future, the Eurozone and the EU may see a new wave of fiscal expansion, and a return to the highly indebted mode of operation.

Prospect of Franco-German axis and Eurozone reform

The early days of European integration has seen the Franco-German axis serve as the backbone and engine of Europe. The election of Macron as the President of France in May 2017 threw the German political circles in a jubilant mood. They held that Merkel, and Macron, a “European hero” who shares a similar governing philosophy with the iron lady, would return Europe to glory.

Macron has, since taking office, has rolled out dozens of specific reform policies. However, in this French-led reform of EU integration, Germany, with a complicated political landscape at home, tended to show little enthusiasm. Then, before the summer summit of the European Union in 2018, Merkel and Macron agreed on a plan for a unified budget for the Eurozone in the hope of establishing a common budget system from 2021, so as to create a more stable competition environment and promote coordinated economic development within the area.

The plan, though warmly praised by Jean-Claude Juncker, president of the European Commission, and Mario Draghi, president of the European Central Bank, was abandoned due to opposition from the 12 member states, including Netherlands and Belgium. Thus, it can be seen that the reform of the Eurozone still faced tremendous resistance, and the day of success was far away.

The structural reform of EU political organizations, joint defense at the military level, and policy adjustment in the field of trade, among other issues, all require Germany and France, the two major economies of Eurozone, to make concerted efforts to lobby other countries for the consummation of an agreement. However, there is still a big gap in the core issues of the reform plan between Germany and France, as evidenced by the relatively conservative attitude toward the size of the European monetary fund, and a lack of enthusiasm for the European common defense system on the part of Germany.

Given the difficulty of reaching tacit agreement with Mr. Macron in the short run, Ms. Merkel might choose to leave these important issues to the new leaders of CDU. Meanwhile, German conservatives have been divided over Macron’s unified budget proposal. It also means the deal reached between the two leaders in June would come to nothing amid the regime change in Germany. Mr. Macron, having lost an important ally, will face a harder time in his effort to reform the Eurozone.

Conclusion

In those 13 years, Merkel had, to some extent, represented the stability and continuity of traditional establishment politics, according to comments from the Guardian. In this sense, her departure also marks the complete end of a political era. For Europe, “It will be the most dangerous moment since World War II.”

For Germany, the issue is how to stabilize domestic politics in the post-Merkel era. For France, the challenge is how to push forward Eurozone reform in collaboration with Germany again. In addition, it remains unknown whether Italy will challenge the authority of the EU’s fiscal rules in a more brazen manner, whether Europe will pay as much attention to voices from Berlin as it once did, whether there will be more ferocious populism, and how the world is going to deal with a changed Europe.

The information contained in this website is of general nature only and does not take into account your objectives, financial situation or needs. Please ensure that you read the Financial Services Guide (FSG) , Product Disclosure Statement (PDS) , and Terms and Conditions which can be obtained on our website https://www.aetoscg.com.au, and fully understand the risks involved before deciding to acquire any of the financial products listed on this website.

AETOS Capital Group Pty Ltd is registered in Australia (ACN 125 113 117; AFSL No. 313016) since 2007 and is a wholly owned subsidiary of AETOS Capital Group Holdings Ltd, carrying on a financial services business in Australia, limited to providing the financial services covered by the Australian financial services licence.

Trading margin FX and CFDs carries a high level of risk and may not be suitable for all investors. You are strongly recommended to seek independent financial advice before making any investment decisions.

This commentary is owned by AETOS, and copying, reproduction, redistribution and/publishing of this material for any purpose in whole or in part without the prior written consent of AETOS is prohibited.