Globalization is often spoken of as a major sea change over the past four decades or more. Technology and telecommunications advances have made the world a more connected commercial marketplace, more so than ever before in the history of mankind. The process has redistributed wealth across the planet, cut global poverty in half, and made a multitude of Small to Medium-sized Enterprises (SMEs) active participants in international trade. While SMEs may have seen the market for their products and services expanded greatly, owners have had to deal with a new form of risk – foreign exchange volatility.

Yes, forex rates are anything but stable. Depending upon your mix of imports and exports from various overseas markets, you may see fluctuations in applicable currency rates that can severely impact your profit margins or even your ability to stay in business, but have you taken any action in the past to protect your business against wild swings in market forex rates? If you said “No”, you were not alone. In a recent survey taken by American Express, they spoke with 1,000 owners of SMEs in the UK, and 43% of them said that they had done nothing.

The UK is only one market, although a very developed one that is very active in global trade. Surprisingly enough, in that same survey, 42% of respondents said that they knew they had lost money due to foreign exchange. Per Forbes:

One survey published last year suggested Britain’s small businesses may collectively be wasting £10 billion a year by failing to effectively manage their exposure to currency movements.

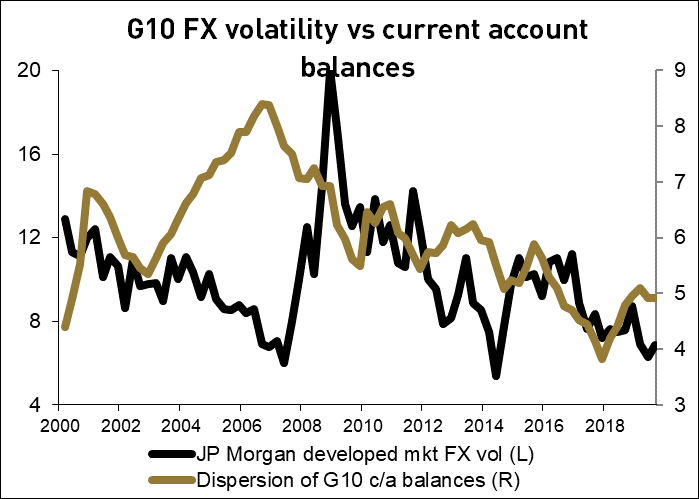

Source: nasdaq.com

The inference from the above chart, provided by Nasdaq.com, is that small business owners may have been lulled into a false since of security over the past few years. Developed currency pairs have been fluctuating less. FX volatility has been in decline. The press has focused more so on the issue in the UK due to Brexit discussions, which have brought a high measure of uncertainty and damaged the value of Pound Sterling in currency markets. Based on the recent Conservative Party victory, however, the Pound has improved to levels not seen since pre-Brexit, but volatility is still the issue.

What if your business deals with emerging markets or is situated in one?

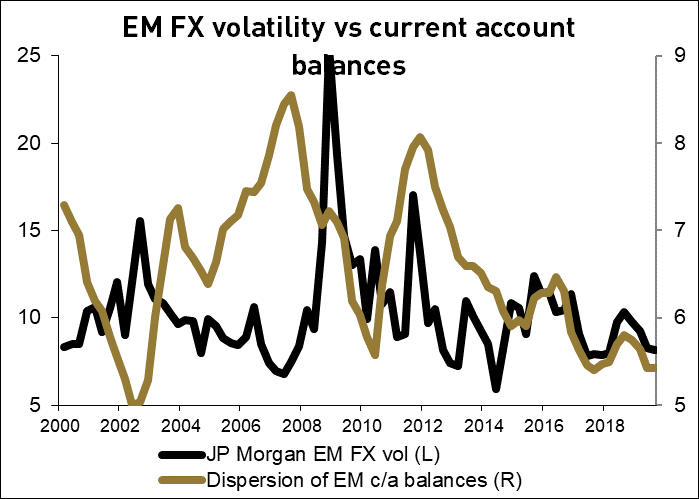

Forex volatility has followed similar trends, as per this companion slide:

Source: nasdaq.com

Once again, current account balances have stabilized, which has led to a dampening of forex market fluctuations and fewer opportunities for traders and speculators. Observers attribute this “calm” to global monetary efforts of central banks over the past decade, but the same observers are now calling these efforts the “calm before the storm”. Inflation, higher interest rates, and possibly recession could be lurking just around the corner. We could see forex volatility leap into higher double digits, as a harbinger of these events.

How can a small business be disadvantaged?

It all depends on your cash flows to and from overseas markets. The risks can be “netted” to advantage, if possible, but your net exposures to foreign markets defines your “fx risk” potential. It is often said in the press that a weaker currency favors exporters because their products will be cheaper in foreign markets. The opposite would be true for importers. Prices rise under this scenario. If your domestic currency strengthens, as the GBP did recently, then the reverse of the above statements is true.

Unfortunately, exporters with a weaker currency sometimes see their sales decline instead of rising, as their customers overseas search for alternatives or reduce their dependencies. An importer example, however, might drive home the point more clearly. In this case, the cost of foreign purchased goods increases. The SME must make the decision early on as whether to raise prices and risk losing customers or allow the increased costs to eat into his margins.

This particular issue has happened in the UK. Per Forbes again:

Just over three years ago, before the Brexit referendum, £1 was worth $1.50 – today it’s down to $1.21.

It now rests at just above $1.33. Imagine for a moment that your cost of goods sold went up 20%. What would you do? Forbes spoke to two SMEs that had to face such a reality. Here were their responses:

- Patrick Dudley-Williams, founder of tie and clothing company Reef Knots, who spent three years cutting costs to survive: “It’s no longer sustainable to absorb cost increases. We are getting to a stage where we are going to have to raise prices.”

- Danny Michelson, owner of London-based cheese shop La Fromagerie, who imports the majority of his goods from Europe: “We are always behind the curve when the pound is falling, because the effect is immediate, whereas altering our prices to counteract that can only be done gradually.”

When the Pound suddenly strengthened, could Mr. Dudley-Williams above have loaded up on inventory to take advantage of the advantageous change? The answer is two-fold:

- An FX surge is often short-lived and trying to time it with subsequent actions can prove fruitless, and

- Small businesses typically work off cash and are strapped for this type of buy.

Per Mr. Dudley-Williams:

We want to fund our growth but if our margins are squeezed because of the exchange rate, I don’t get much sleep.

Owners of SMEs often cringe with anxiety when they hear the word “hedge”, but larger firms have treasury departments with expertise in the art and have found ways to limit their foreign exchange rate risk exposures by hedging. The process can be as complex or as straightforward as you wish to make it, but the process starts by understanding your projected cash flows to and from overseas markets by currency. If you can protect yourself in your contract to deal only in your local currency, so much the better, but often your client might shop elsewhere instead of taking on your forex risk.

Once you have your flows, both in and out, spread over time, you may then “net” each month or quarter depending on how detailed you wish to be. In the case of the cheese merchant above, he has major recurring outflows in Euros. Hedging could be as easy as buying “forwards” for Euros from his bank that match his projected outflows. He would then “fix” his rates for these future outflows, but at today’s exchange rates. If the Pound moved in his favor, he would not benefit under this scenario, but he had “fixed” his exposure risk for the following 12 months. His costs would not fluctuate wildly.

What would a treasury specialist do under these circumstances? In the case of the cheese merchant, his bank might require that capital be set aside to cover the bank’s risk when issuing forwards. A better way to go is with an “option”. The process is the same, but you must purchase options instead of forwards, hopefully, from your bank’s cash management service. If the Pound weakened, you are protected. You exercise the option at your “fixed” rate. If the Pound strengthens, you benefit, as well, by letting the option expire. You are only out the cost of the option.

Hedging can be complicated, but your trusted banking partner should be able to guide your process or recommend a trusted third party. Security is major issue. Do not go with an intermediary that you are not comfortable with. At the end of the day, hedging is like insurance. There is a cost, a premium if you will for the option, but gains can offset those costs. There is, however, a saying in the hedging world that not hedging material risk exposures is tantamount to gambling, the reason UK SMEs wasting £10 billion last year.